19TH SESSION OF THE ASSEMBLY OF STATES PARTIES

Friday 11 December

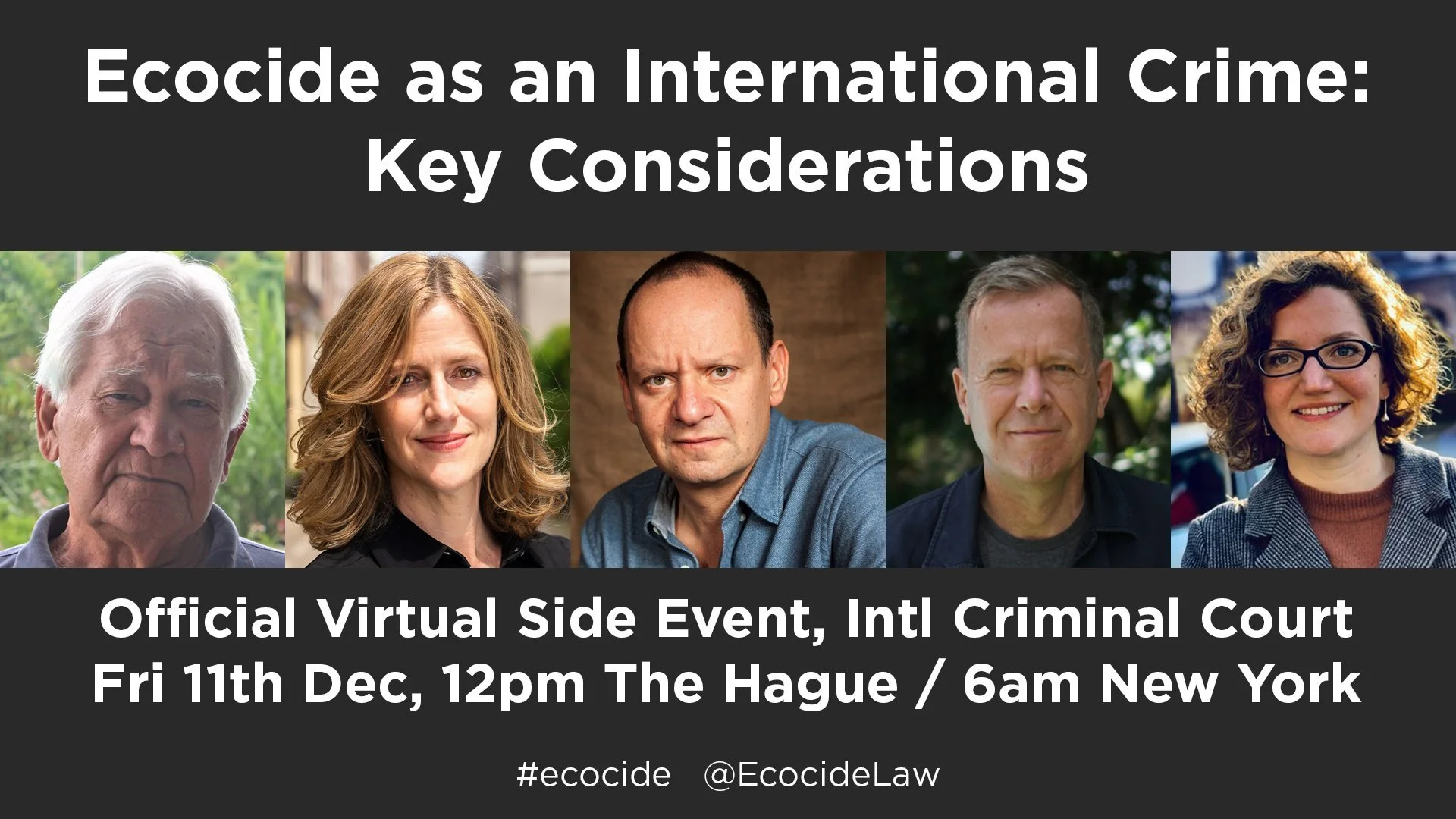

Name of the Side Event: Ecocide as an international crime: key considerations (co-hosted by Stop Ecocide Foundation, Institute for Environmental Security & Vanuatu)

Report by: Isabelle Jefferies, Junior Research Associate PILPG-NL

Main Highlights:

At the 18th ASP in 2019, the small island States Parties of Vanuatu and Maldives addressed the urgent need for “Ecocide” to be incorporated into the Rome Statute. In essence, this would criminalize mass damage and the destruction of ecosystems. The movement gained momentum, with prominent states such as France and Belgium expressing their support for the cause.

In November 2020, a panel was convened by the Stop Ecocide Foundation to draft a legal definition of Ecocide as a potential international crime that would sit alongside genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

The drafting process will begin in 2021, and this event covered the key legal, historical, and political implications of the proposed plan.

Summary of the Event:

The event was co-hosted by the Republic of Vanuatu, the Stop Ecocide Foundation, and the Institute for Environmental Security. A distinguished panel of speakers, including three members of the drafting panel, gave their views on the proposed plan to adopt a legal definition of ecocide. The panel consisted of Philippe Sands QC, barrister at Matrix Chambers and Professor at University College London, Kate Mackintosh, Executive Director at the Promise Institute for Human Rights and Professor at UCLA School of Law, Marie Toussaint, Member of the European Parliament (Greens/EFA), and Judge Tuiloma Neroni Slade, former ICC judge. The event was moderated by Andrew Harding, Africa correspondent for the BBC.

Mr. Dreli Solomon, representative of Vanuatu, welcomed the attendees by emphasizing the seriousness of the ongoing climate crisis, and recalled the importance of solidarity if progress is to be achieved. Mr. Pekka Haavisto, Finland’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, also stressed the seriousness of the ongoing climate emergency. He added that the small island states of the Pacific and the Indian Ocean are the first to suffer the consequences of the changes we are seeing in the climate, and they desperately need the support and reaction of the international community.

Each speaker was asked to give some introductory remarks. Mr. Philippe Sands QC began by paying tribute to Polly Higgins, one of the most influential figures in the green movement, who continues to inspire those involved in the development of the crime of Ecocide. Prof. Sands will chair the ecocide drafting panel, and started by giving some context to international criminal law. Before 1945, war crimes were the only codified international crimes. fter the Second World War, new crimes were created, and were applied retroactively to those accused of atrocities, namely, crimes against humanity and genocide. Mr. Sands was persuaded to participate in the drafting panel for Ecocide as he recalled Raphaël Lemkin and Hersh Lauterpach, two crucial figures in the drafting of the above-mentioned crimes. They were crucial in the enactment of these crimes by bringing their ideas to the table, and he hopes to do the same with ecocide.

The extensive impact of human activity on the environment only began to enter into the consciousness of people around the world in the 1970s with the Stockholm Conference. Crucially, in 1996, in the Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, the International Court of Justice stated that the protection of the environment is part of customary international law. Twenty-five years later, the extraordinary challenges we face as human beings, and that are faced by the ecosystem and all they contain, are more prominent than ever. Prof. Sands emphasized that the time has come to harness the power of international criminal law to effect change for the better. He emphasized that he is not starry eyed, and that he is aware that there will be many challenges. Notably, he is concerned about using the definition of genocide too closely in the drafting of Ecocide, as the former requires that the intention to destroy a group in whole or part is proven, and this is complex. Therefore, the drafting panel, whose terms of reference are strictly restricted to coming up with a definition of Ecocide, must take the best from the definition of crimes against humanity, the best from the definition of genocide, and perhaps some aspect from war crimes. They must then meld from this something workable and effective. In other words, the legal definition of Ecocide must not be overly onerous, but on the other hand, it must not open the floodgates. It must deal with real situations, when one or more human beings recklessly, or with intent, proceeds to destroy the environment or a part of it, on a massive scale. Prof. Sands is satisfied with the composition of the panel, as it is very broad ranging, which will allow for a constructive debate. He assures stakeholders that the panel will have a close regard to the practice of international courts and tribunals in order to come up with a feasible definition in the next six months.

Kate Mackintosh, also a member of the drafting panel, continued the discussion with her introductory remarks. She first introduced the history of Ecocide, a term that was coined by Professor Falk in 1973, when he proposed an International Convention on the crime of Ecocide in response to the use of agent orange and environmental destruction during the Vietnam war. Prof. Falk had drawn his inspiration for his definition of Ecocide from the Genocide Convention. Moreover, the destruction of the environment during armed conflict or for other hostile purposes was then prohibited by two new conventions, namely the First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions (1977), and the Convention on the Prohibition of Military or any other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (1978, ENMOD). Also, in 1985, the UN Committee on the Prevention of Discrimination and the Protection of Minorities proposed broadening the definition of genocide to include adverse modifications to the environment, which threaten the existence of entire populations, such as through nuclear explosions, chemical pollution, acid rain, or the destruction of rain-forest. Prof. Mackintosh drew the attention of the audience to the fact that there is a contrast between these definitions: some are anthropocentric, whereby the elements of the crime require harm to humans, and others are eco-centric, whereby harm to the environment is enough in itself. This is an issue which the drafting panel will have to deal with. Moreover, she recalled that the Rome Statute references the war crime of causing long-term, widespread and severe damage to the natural environment in international armed conflicts. However, this is subject to the proportionality test of anticipated military advantage. In drafting a legal definition of Ecocide, the panel will draw inspiration from the above mentioned sources.

Prof. Mackintosh then touched upon the issues that will be taken into consideration by the panel. She referred to the work of a committee of experts on international criminal law that convened in early 2020 at UCLA. The first issue she anticipates is whether the panel should go for a broad definition that catches climate change, or a more narrow focus that focuses on massive environmental damage. The second issue will be whether harm to the environment should be punished per se, or whether it has to be linked to human harm. The anthropocentric approach is limited given that it can take time for the harm caused to humans as a result of environmental damage, to show. Lastly, ecocide would need to be forward looking due to the principle of legality. However, this brings the risk of skewing responsibility unfairly towards the Global South, so the panel may need to come up with a similar principle to the Common but Differentiated Responsibility adopted by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Marie Toussaint continued the introductory remarks by noting the revolutionary nature of the ecocide drafting panel. Although she predicts some legal difficulties in the drafting process, she believes it has the potential to change the way in which humans apprehend and interact with nature and ecosystems around the world. In August 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron denounced the inaction of Brazilian President Jair Bolsorano concerning the deforestation of the Amazon. He used the word Ecocide to describe the events, allowing the word to gain traction. However, Ms. Toussaint noted that despite the President committing to pushing for the recognition of Ecocide at the international level in January 2020, nothing has been done in this regard. Moreover, the Yellow Vest Movement saw people take to the streets and demand fairer climate policies, that are currently deemed to be too strict on the poorest levels of the populations, and too lax on the richest even though they are often the ones that pollute the most. Yet, she believes that the French government is refusing to recognize the intrinsic value of nature, and that for them, nature is merely something to serve the interest of human beings. Ms. Toussaint stressed that Ecocide should not be emptied of its content, especially in the national jurisdiction of a state that is hoped to be a big supporter at the international level, such as France.

However, France is not the only purported supporter of Ecocide. In Belgium, Samuel Cogolati presented a motion in the national assembly which seeks to recognize Ecocide within the national law, and support it as an international crime at the ICC. A new government was formed, but they are still working on this proposal. This is a huge step forward, especially as a member state of the European Union. She further spoke about the important role of Sweden in the creation of the drafting panel. Ms. Toussaint stated that she would like to see EU commitment to support the recognition of Ecocide at the international level, and also within EU law. This can be achieved through a new Regulation for the recognition of Ecocide, or through the revision of a 2008 Directive on the Protection of the Environment for Penal law. She concluded with a call on participants to get in contact with their local parliamentarians, if they are honest and committed to the environment, to join the ecocide alliance.

Tuiloma Neroni Slade, who has spent decades fighting for the rights of small island states, was the last to give his introductory remarks. As a Samoan, he emphasized his personal perspective on the relevance of Ecocide. He spoke about the Pacific islands, and how they have been misused and abused, mostly through the careless nature of human activities. He used the example of plastic, which has been recognized as a global issue since the 1960s, but the problem has expanded disastrously. He also talked about the disastrous destruction of coral reefs on a massive scale, due to bleaching that is caused by ocean acidification. Other factors that substantially compelled the Pacific’s precarious environmental situation are that it was used as a theatre of war for Western nations. Judge Slade stressed that the Pacific communities had no part in the causes of war, yet they became the object of the atrocities and the scourge of war. The pacific was a testing ground for weapons of mass destruction.

In support of the concerns expressed by the representative of Vanuatu and the Maldives at the 18th session of the ASP, Judge Slade emphasized that small islands states are the least responsible for global carbon emission, yet, they are among the first and most severely impacted by the consequences of the climate crisis. Their predicament is made worse by their precarious living situations, they are small communities that do not have the coping capacity, or the resources and technology to defend themselves from the disasters that occur as a result of the changes in the climate. He further mentioned cyclones, and the devastation they bring. For instance, Vanuatu lost over 65% of its GDP to Cyclone Pam in 2015. As science has predicted, these so-called “super-cyclones” have become more destructive in their frequency, and in their high wind intensity. The struggle for survival is real, so people face the inevitable choice of out-migration and leaving islands altogether. Judge Slade stressed that the Alliance of Small Island States fear that what is happening to them, will inevitably happen to others, as demonstrably is already happening around the world. He concluded with expressing belief that small islands should serve as the global frontline warning system to others.

The event then moved on to a Q&A session, during which participants were given the opportunity to present their questions to the panelists.The first question was as follows: why is it more advisable to invest time and resources in establishing a crime of ecocide than in making better use of existing norms and procedures to address environmental destruction? Prof. Sands provided his thoughts and stressed that the crime of Ecocide should not be seen as a “magic bullet” that will solve all the issues surrounding the climate crisis. However, criminal law is a useful tool which will raise consciousness as to the seriousness of the issue at hand. He noted that the Rome Statute could be amended, and a new category of crimes against humanity could be created. However, words matter as proven by the attention that is captured when the word genocide is used. By contrast, the word crime against humanity does not get as much attention. However, he is adamant in the necessity to move away from the anthropological definition of ecocide.

The second question put to the panel was the following: if ecocide is criminalized, how would the continued refusal of the US to sign on to the Rome Statute affect the potential to prosecute US corporations? Prof. Mackintosh gave her views on this and she stated that the ICC has a number of alternative bases for jurisdiction, with the principal ones invoked being territory and nationality jurisdiction. Hence, if US corporations were to have subsidiaries in a state that is a State Party to the ICC, the latter would have jurisdiction to examine, investigate, and possibly prosecute the crimes they are alleged to have committed. Also, the ICC has used an “effects” approach, whereby if the effects of a crime are felt in a State Party, the ICC has jurisdiction.

Moreover, the panel was asked to share its view on national initiatives to define Ecocide in their national legislations, but that may not seize the full magnitude of the offence and may therefore prevent further legal evolution or from efficient prosecution of on-going serious harm to the environment. Prof. Sands explained that the international arena is only going to be a backstop for the criminalisation of Ecocide. In fact, it is for national courts to deal with this primarily. As a result, the role of the Ecocide drafting panel is to come up with a definition that works domestically.

Lastly, the panel was asked to give some examples of initiatives that they believe could be taken by attendees to support the codification of Ecocide as an international crime. A general consensus among the panelists was that those committed to the codification of Ecocide as an international crime should write to their relevant members of parliament, and push them to support the cause. Prof. Sands also told attendees that the drafting panel would send out a call for submissions when they begin their work in early 2021. Marie Toussaint recommended attendees to support the Stop Ecocide campaign and to sign petitions. Jojo Mehta, co-founder of the Stop Ecocide Campaign, concluded that the use of the Ecocide in itself, to describe the mass damage to nature, cannot be undermined.